Growing Up On The Farm

Story furnished by Clarence Crocker

Some eight or ten years ago, my baby daughter, Kathy June, gave me a memoir book for Christmas with a note attached which read, Daddy, give me and Wayne a real Christmas present. Write some of your “growing-up” memories down for us and your grandchildren. Judy, my first child died in 1993. Their mother died in 1994. Since then I have tried to jot down some of my life’s experiences as older age has taught me the value of such. At the suggestion of some of our web site readers, I have released this to the Glendale and Pacolet Memories websites.

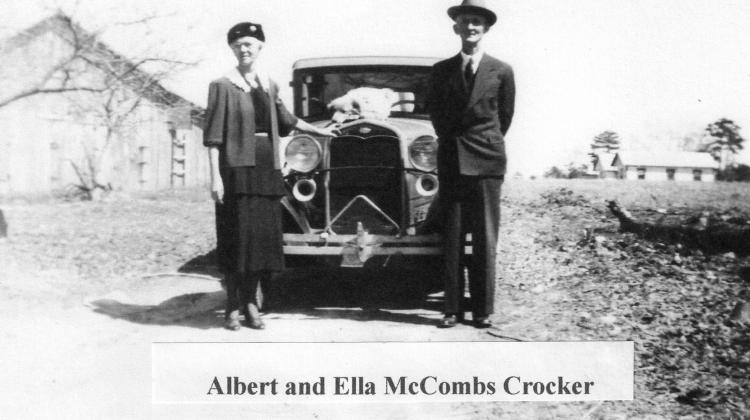

There were eleven in our family. Our dad, Albert E. Crocker, died September 28, 1974, at the age of 84. Our mother, Ella McCombs Crocker, died May 17, 1976, at the age of 85. Juanita Crocker, my only sister, died January 15, 1912, at the age of 42 months. My twin brothers, George Reon and Albert Leon Crocker, died as infants on April 16, and April 23, 1918, respectfully. My baby brother, George Smith Crocker, died on May 2, 1932, at the age of 17 months. My brothers, L. Eston, died February 14, 1995, at the age of 80, Paul R., died October 20, 2000, at the age of 81 and James Vernon, (J.V) died February 17, 2002, at the age of 85. Albert W. lives today, at the age of 89 and I was 87 on November 5, 2011.

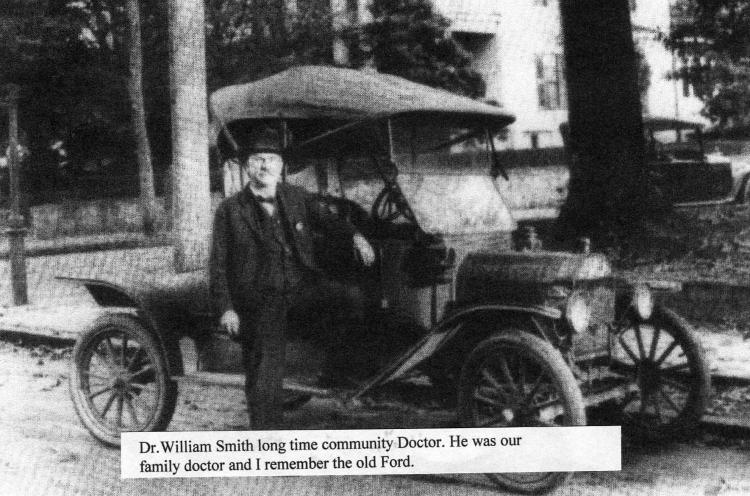

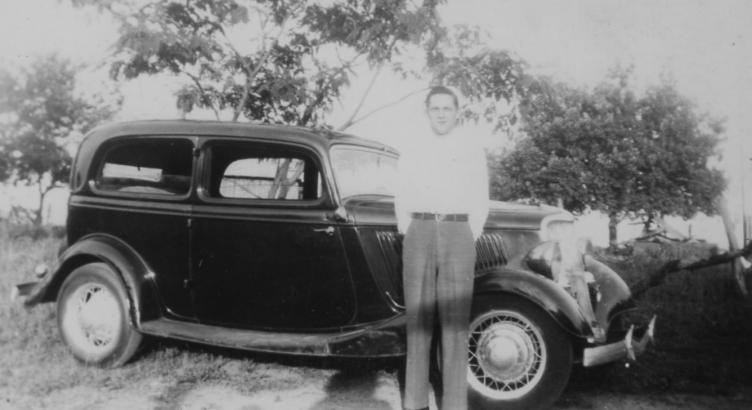

The nation was immerging from the effects of WW1 when I made my debut on November 5, 1924. According to a magazine given to me by my granddaughter, Deni Crocker Pifer, on my birthday, Calvin Coolidge had been elected President. The average yearly income was $1266.00. The national average 4 room house cost about $4,000.00, a new Ford cost $290.00 (See photo above.), a loaf of bread 9 cents, a postage stamp 2 cents and a gallon of milk, 54 cents. I became one of 114,109,000 Americans on that day. Dad was a weaver in the textile mill and being a skilled carpenter he also did carpenter work on the side. He helped build Camp Wadsworth and the Montgomery Building in Spartanburg. I got a horn from Santa Claus on the first Christmas that I remember on the farm. Of course I also got a few other toys, some clothes, oranges, apples, nuts and candy along with a big cluster of dried raisins.

Clarence at about 4 years old.

The great depression of the thirties was in full bloom when I was a lad. Jobs were scarce and money was even more so. Soup kitchens and welfare lines were growing every day. A can of sardines cost 5 cents and a small box of saltines 3 cents. Many cars were still being started with a hand crank. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCCs) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA, nicknamed, “we poke along”) had been started by the Federal government to give people jobs. One of the requirements of the CC Corp was that a portion of their earnings had to be sent back to the family at home. Clothes “hand-me-downs” was the common practice except in cases where the mother made many of the clothes, as did our mother. Mother used cloth from Queen of the West flour and feed sacks to make shirts, sheets, etc. Some cloth was beautiful steadfast floral print. We did not lack for food as many. We grew most of our meat and vegetable food needs. Like most families of that day, we caught fish from time to time as well as killed wild rabbits and squirrels.

We did not live on a large farm, just a small acreage one horse family farm. Our first work horse was named John. He was a good plow horse but could get awful stubborn at times. My cousin was plowing with him one day during his stubborn spell. My cousin, in desperation hollowed out, “John you are as crazy as I am” to which his brother hollowed, “Poor John”. Following John’s death, dad purchased a mule named Nell which we kept until we quit farming. We had no automated machinery such as tractors, mowers, cotton pickers, threshers, etc.

Our home was a modest six room house. It had a large screened back porch and a front porch that ran almost the width of the house. We had one half of the front porch screened to keep the mosquitoes from eating us up while sitting on it at night. In the summer time, we boys oft times made a pallet on the floor on the porch and slept there at night and in the afternoon. Oft times we would simply lie on the grass under a shade tree when we took a break from the field during the heat of the day.

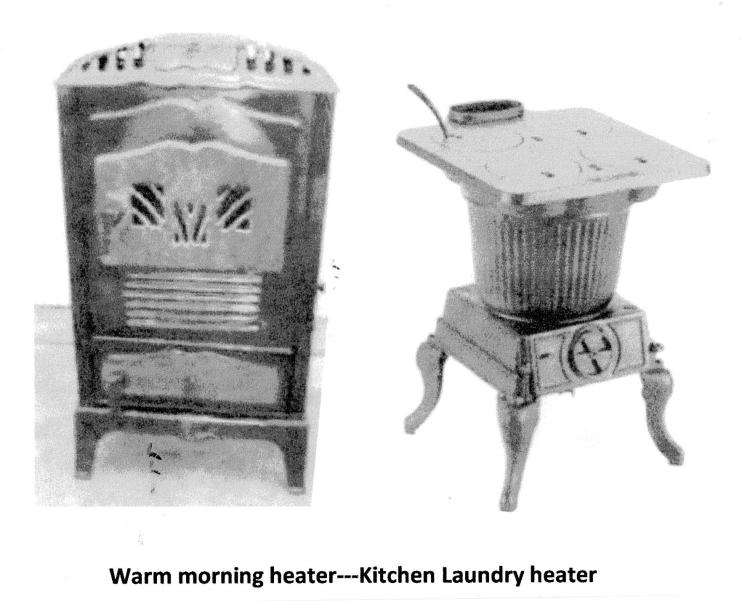

In the early days (1920-30s) our home was heated by a wood cook stove, a laundry heater and grate fire places. We later got a Warm Morning coal heater which did an excellent job of keeping the whole house cozy. We drew our water from a 65 foot bored well which had extremely cool fresh water. I miss that cool fresh water today. We took our baths in large metal tubs. We boys slept on an iron frame bed with a straw tic over coil springs topped with a feather mattress. Our mother made the tics using wheat straw and the mattresses using chicken feathers. We had no running water until the late thirties and our rest room was the old common outdoor privy.

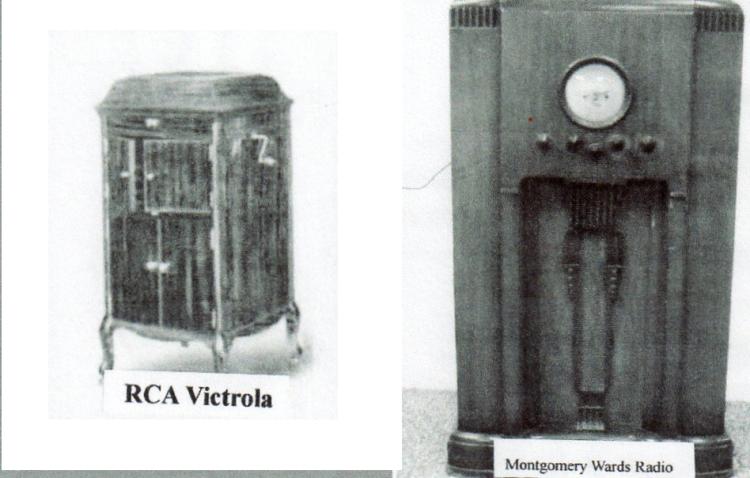

Our home entertainment center was limited to a Wards radio and a R. C. A. Victrola record player which played twelve inch black disk records which could be purchased in Spartanburg or ordered from catalogs. We had a few country western records but most were religious quartets or solos. Amos and Andy, Lum and Abner were two of our favorite radio programs. Television wasn’t on the market in South Carolina in those days. We looked forward to the catalogs from Montgomery Ward, Sears Roebuck and Spiegel in the spring and fall. Also the Parks and Hastings seed catalogs which provided useful information for home and farm. They were also a good source to occupy the time on a long lonely rainy day or night. Our games were limited primarily to baseball, football and marbles. We used slingshots to shoot birds and squirrels. I got a Daisy air gun for Christmas when I was about eight or nine years old. My older brothers had 22 rifles.

We also popped popcorn and Mama would make molasses candy to munch on during those cold winter nights. Though we had electric lights, we did not get an electric refrigerator until about 1935. Until then, we used an ice box and a cistern located beside our well which we kept filled with cool fresh well water to keep our milk and butter cool. We purchased an electric stove in the late thirties. We had no telephone for many years and when we did get a phone, it was a party line which meant you had to pick up the phone to see if it was busy before cranking for the operator to give her the number to get your party

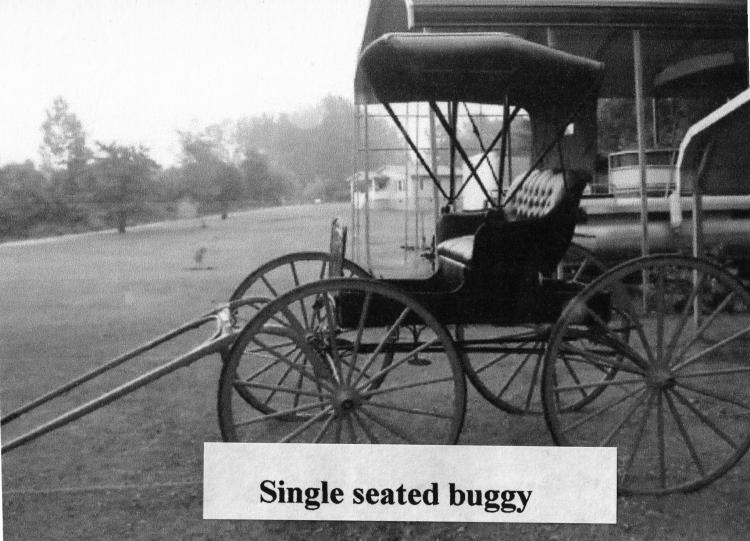

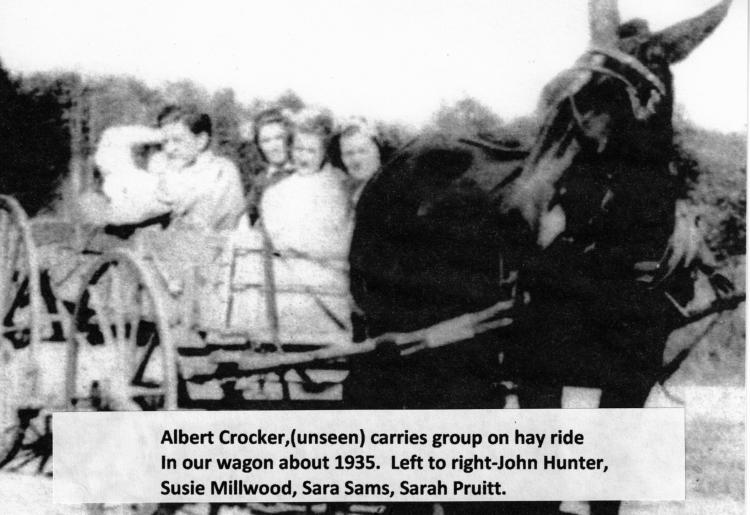

Our mode of transportation was primarily the buggy and the Trolley car. We rode horse back to the grocery store occasionally. When Dad and Mother were going to Spartanburg in the buggy one of us boys went with them. Dad would hitch the horse at Cudd’s Livery Stable located just off Main Street. For ten or fifteen cents they would water the horse/mule and hitch them in the shade. For about a quarter, they would put the horse in a stall and feed it. When in town, Dad would most always carry us by Blue Bird Ice Cream store down on the square across from the bus stop for a cone of ice cream. I believe it cost about 5 cents. Dad walked about a mile each way going to and from work in the Glendale Cotton Mill.

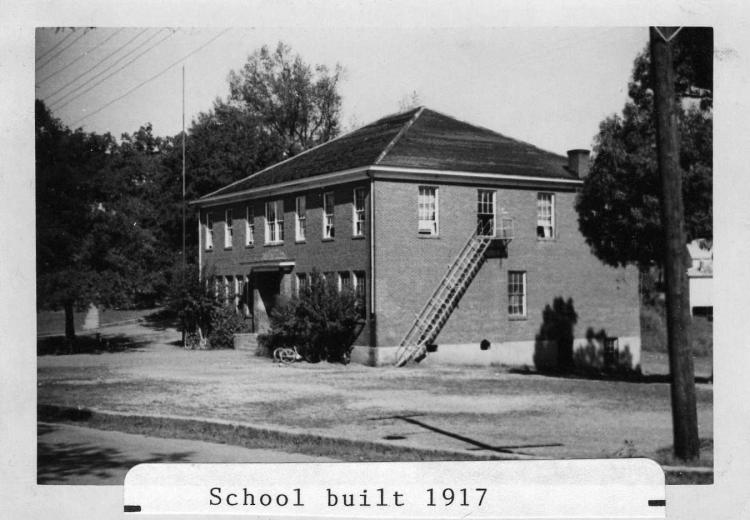

Rain or shine, all of us boys walked back and forth to the Glendale Elementary School, which was located about a mile from our house.

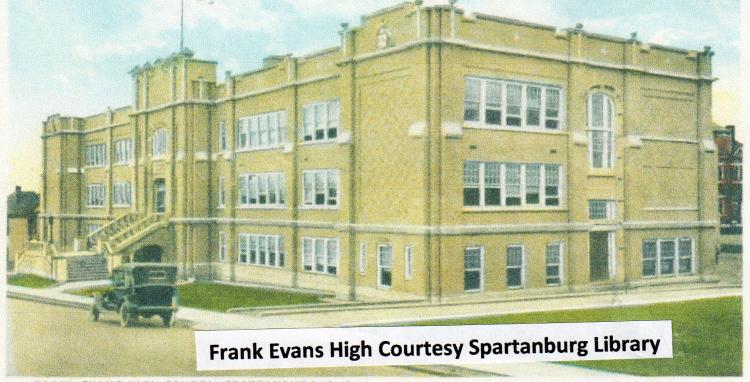

Not until we started to Frank Evans High School in Spartanburg did we ride a bus. We rode in the wagon when we were carrying wheat and corn to White’s Grist Mill or cotton to the Zion Hill Cotton Gin or picking up fertilizer from one of the farm supply stores.

About the mid-thirties Dad bought the first and only car he ever owned, an A Model Ford sedan. My brothers, Eston, J.V. and Paul drove the car. Albert and I were too young to get license. On one occasion J.V. carried dad out to teach him to drive. When Dad got under the wheel, he had not driven but just a short distance before he got nervous and lost control of the car, J. V. took over and Dad never tried again.

Mama cooked on a large wood cook stove which had a water tank on the right end which we kept filled for hot water needs 24/7. The stove burned pine cord wood which we kept split and cut into about 15 to 18 inch lengths. One of my jobs was to help keep the wood bin on the back porch full. The stove would also burn coal.

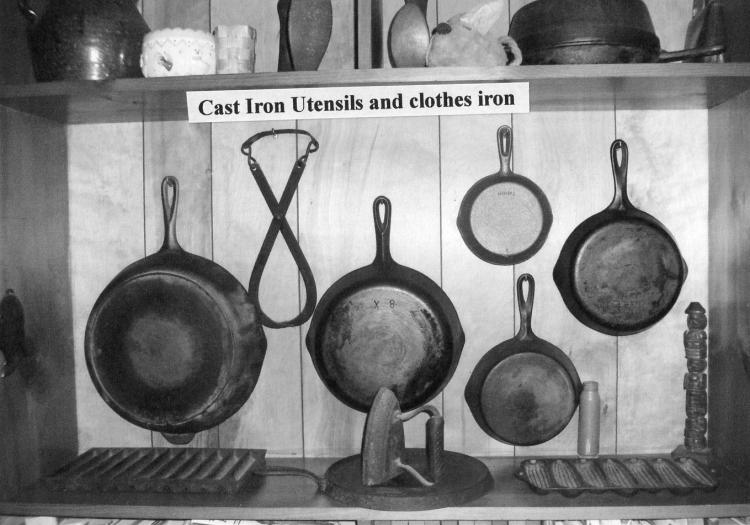

Mother’s primary cooking utensils were cast iron. The stove had a warming oven at the top in which she kept warm biscuits, cornbread, baked sweet potatoes, fried sausage or ham, most times. A local Preacher, Rev. Curtis Holland, who made himself at home when he visited, would oft times come through the turnip patch, pull him a large turnip or two, come to the house, get him 3 or 4 biscuits and eat them with big slices of salted raw turnip.

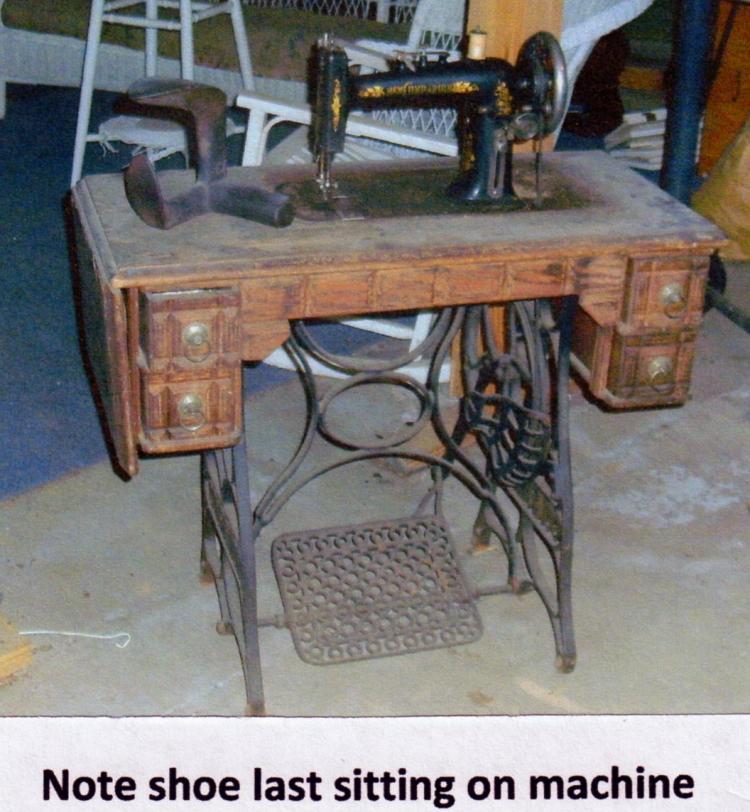

Mama was an excellent seamstress. Using a foot peddle sewing machine she made most of her clothes as well as our baby clothes. She continued to make many of our clothes as young boys, especially our shirts. She washed clothes in a large black iron pot, filled with boiling water and rinsed them in wooden tubs made from fifty five gallon molasses barrels, cut in half. She used a metal ribbed rubbing board to scrub the clothes when needed. For many years she used a cast iron, heated on the stove or in the fire place, to press our clothes. Mama also used the big black iron pot to make corn hominey. Using a steel shoe last, Dad would put new leather or rubber soles on our shoes or boots when they wore out.

At this point, I am reminded of a sad incident. It was in one of the wooden barrels that my baby brother George was drowned. We kept one or two half barrels in the chicken lot under the roof of the chicken house to catch water for the chickens and also to keep the barrels swelled to keep them from drying and cracking. The gate was to be locked at all times. Unbeknown to any of us, the gate had been left unlocked, obviously through oversight. George got into the lot and playing in the water, apparently lost his balance and fell headlong into the 18 inch deep water and drowned.

We boys each had a hobby by which we made our spending money. Children’s allowances weren’t heard of in those days, at least not in our family. Eston, my oldest brother, raised and sold pure bred registered homing pigeons. He shipped them to various places to prove their homing instincts and had many prize winners. The government sponsored programs for homing pigeons as they were still being used by the military. I understand they were the principal message carrier during the early wars. J. V., my next oldest brother, raised and sold regular pigeons. Paul raised and sold rabbits. They could sell all the pigeons and rabbits they had to sell to the Spartanburg General Hospital through the hospital’s purchasing agent. They were used at that time in special diets for people with certain ailments, especially stomach problems. Albert raised and sold pure bred feather leg bantam chickens. I kept bantam hens for their eggs. At Easter time I could always sell all the eggs I had for Easter egg dying at about ten cents a dozen. They made beautiful Easter eggs.

On the farm we grew wheat, corn, sugar cane, okra, sweet and Irish potatoes, peppers, cucumbers, watermelons, cantaloupes, turnips, peas, beans, cabbage, squash, tomatoes, mustard greens, strawberries, etc. We had peach, apple, pear, quince, damson and plum trees along with grape vines for fruit. Of course we picked blackberries which grew wild on the back side of our place.

Mother, using half gallon and quart glass jars, canned enough vegetables and fruits for our needs in off seasons. Using a large metal tub filled with water, she placed about 24 quart jars filled with vegetables or fruit in the tub and brought the water to a boil thus removing the air from the jars, blanching the fruit or vegetable and then would tighten the lid, sealing the jar air tight. She seldom had a jar to spoil. She also dried apples and peaches. She would peel the fruit, slice it into small slices and lay the fruit on a clean metal sheet in the sun on a roof top for it to dry. According to the weather, it only took two or three days. She made jellies, jams and preserves of all sorts and canned honey which we got from our bee hives.

We had cows for our milk and butter. After the cows were milked, our mother would take the milk, straining it and pouring some into gallon and half gallon jars which she placed in the ice box or cistern for cooling to drink. The other was poured into a churn to clabber to make butter and buttermilk. Corn bread and buttermilk was a favorite evening meal. Though I faintly remember a hand cranked churn which we had when I was a small child, the churn I well remember was a large 4-5 gallon pottery churn in which we churned the milk with a hand dasher. Mother would take the butter from the churn and mold it into one pound cakes for table use. The buttermilk was poured into clean swift gallon lard buckets and was placed in the cistern or ice box with the sweet milk. When a cow calved, if it was a bull we would either sell it for the money or raise it up for veal meat. A heifer calf was most always sold. Occasionally, we would keep one to replace the cow that was aging.

We raised and slaughtered our hogs for meat. The hogs were fed wheat brand, corn and table scrapes. After the hog was slaughtered, dad would cut the hog so as to have hams, pork chops, pork roasts, streak-0-lean (bacon), fat meat and of course, sausage. We had a special room in one of our barns called the “smoke house” in which we put the fresh meat in salt beds for curing. We ground our own sausage, some of which mother cooked and canned. Nothing could beat a good hot sausage or country ham biscuit with milk gravy, eggs and grits for breakfast. We also made liver mush using the livers, corn meal and a little fat for seasoning.

We hatched and raised chickens for meat and eggs. I shall never forget when as a lad of about eight, one of my favorite games was trapping chickens. I would prop a tub up with a stick which was attached to a string which I held in my hand. I would drop grains of corn from out in the yard to the tub and then throw a few under the tub. The chicken would come along plucking the corn up and go under the tub at which time I would pull the string and catch the chicken. One day I pulled the string and the chicken jumped. The tub fell across the chicken’s neck, breaking it. The chicken began to flutter and squawk. Mama saw the chicken and ran to its help. When I told her what had happened, she killed the chicken and I got a good scolding. We also had a few turkeys from time to time.

In the fall, we made a 55 galloon wooden barrel of what we called locust beer. Taking the barrel with a spigot in the bottom, we would place clean bricks in the bottom over which we put 8 or 10 inches of fresh wheat straw to serve as a strainer. Then we would put a 3-4 inch layer of ripe broken locust, then a 3-4 inch layer of ripe crushed persimmons. This was continued almost to the top of the barrel. We then filled the barrel with fresh water and let it stand until the locust and persimmons had flavored the water. Under no circumstance was any sugar added thus it was never intoxicating and it made a refreshing cool drink for midafternoon. Old folk claimed that it was good for your kidneys.

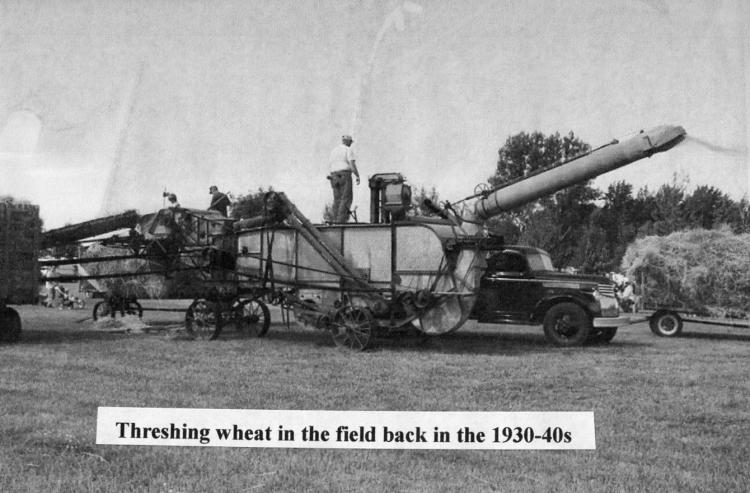

For a few years we harvested the wheat with a hand wheat cradle. It took a strong man to swing that cradle, cutting and gathering the wheat. My brother Paul was about the only one who could stand up to the task for any real amount of time. A man would come around the farms and thresh the wheat for a price or a portion of the wheat. In later years we hired a threshing machine operator to cut and thresh the wheat in one operation. We gathered the corn into the barn to be used for cattle feed and make corn meal, grits and chicken feed.

In the fall, after the wheat and corn had been harvested and threshed, we would take a wagon load to Whites Mill located on Lawson Fork Creek just outside Drayton to be ground. The mill was powered by a water wheel fed by the Creek which turned large mill stones, grinding the corn or wheat. They could adjust the wheels to grind fine, coarse or just crack the grain. The wheat hulls, called shorts, were kept to feed the hogs. Like most other farm dealers in those days, they ground for a portion or for cash. Since cash was hard to come by in those days, most farmers had the wheat and corn ground on shares. The time it took to get your grain ground was according to how many were waiting when you got there but for the most part, you could count on at least, a couple or so hours.

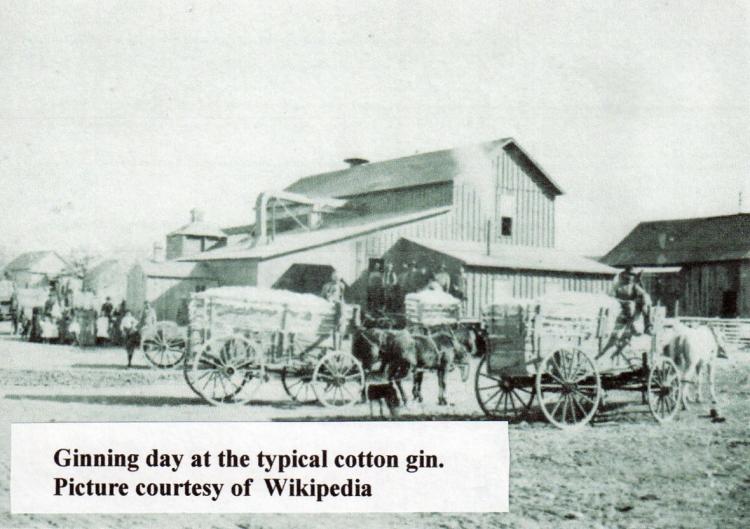

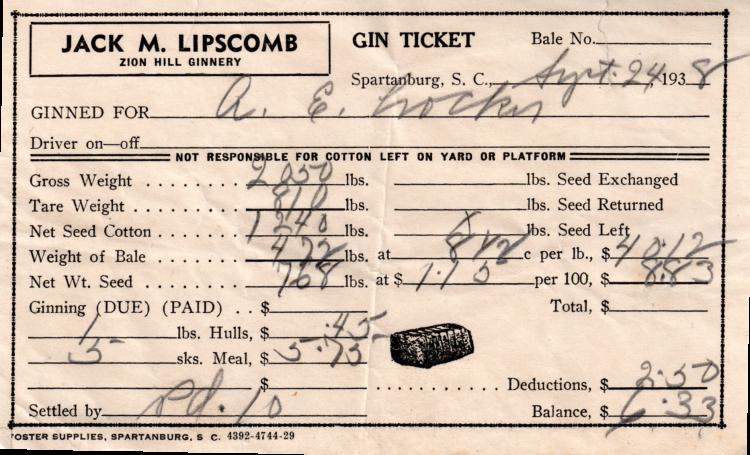

We hired some black people to help pick the cotton. Cotton picking time was County Fair Time. As I have already written, we did not have weekly allowances but Dad would always give us money for the fair. For extra money he would pay us like the hired helpers for picking cotton a week to ten days before we went to the fair. We loaded the cotton, packed down into our wagon with high side beds and would go to the Zion Hill Cotton Gin to have the cotton ginned. Usually there were a number of wagons waiting. When your time came, you pulled your wagon under the large vacuum hose which pulled your cotton into the ginning machines.

The machines separated the fiber from the seeds, bailing the fiber and bagging or grinding your seeds. While we would always keep enough seeds for planting the next year, we had most ground into cotton seed meal for cattle feed. The ginnery, like the corn mill, worked for cash or shares. Bivingsville Mfg. Co. & D. E. Converse Co. operated a gin and a grist meal up into the early 1900s but had discontinued the operations long before my day. Private gins were located in Whitestone and Zion Hill, S. C. at the time I was on the farm.

After gathering the sweet potatoes, the first thing we did was to carry some to the widows and older people in our community. Dad said that was a God given responsibility. We then placed some in wigwams hills behind the barn. The potatoes were piled up in cone shape and potato vines were placed over the pile to keep the potatoes from freezing and then shocks of corn stalks were placed over everything to keep the rain and elements out. The larger part was carried to Mr. Charlie Sams heated potato curing house where they were placed in ventilating baskets to cure which reduced your loss from rot.

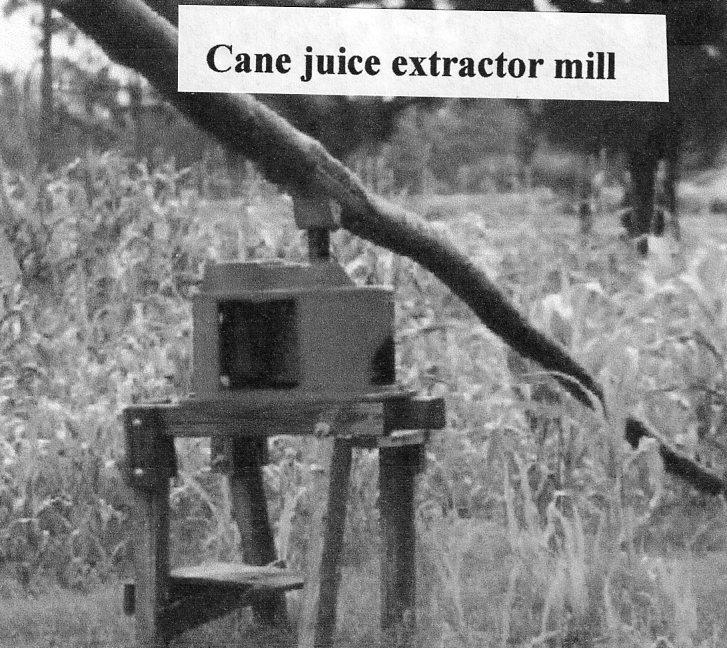

In the fall, after the cane had ripened and been cut, a man with a portable molasses cooking outfit would come around and make molasses. A horse, walking in a circle, would turn the gears which pulled the extractor squeezing all the juice out of the stalks. The juice was poured into vats (4 to 6) on the cooker and brought to a boil, evaporating the water. As the juice thickened, it was moved from one vat to the other until it was fully cooked and thickened. The cattle and horse/mule would eat the stalks.

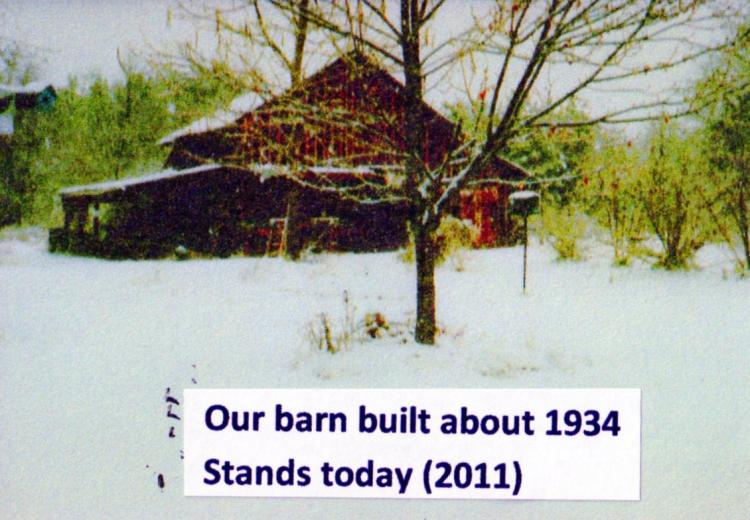

Towards the end of summer before the corn stalk leaves dried, we would pull the green leaves and tie them up in handfuls which we called fodder, to be used as horse feed. We pulled the corn in the fall after it had matured and dried. Our large two story barn had a mule stall, two cow stalls, a corn crib, a huge loft and a large hallway. We would store the fodder and other leafy cattle feed in the loft. The wagon and buggy was kept in the hallway. In the fall and winter months, we would go to the corn crib and shuck the corn as needed for feeding the cattle and to grind for corn meal. We had a hand operated corn sheller with which we shelled the corn. The sheller stands in the barn today.

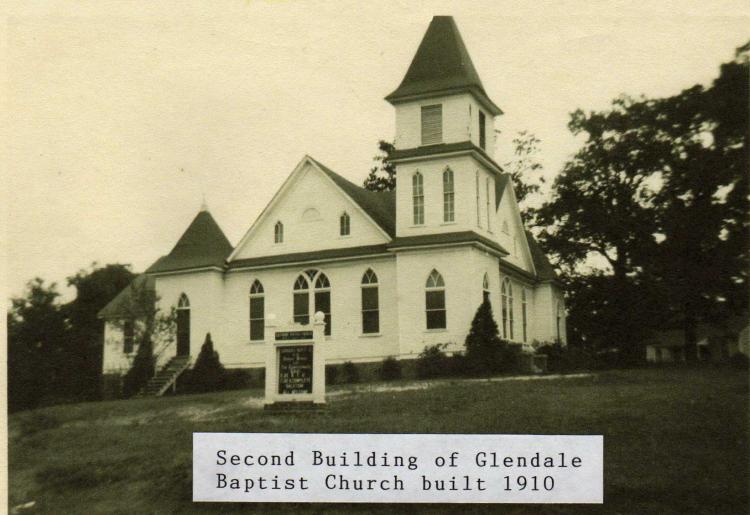

We attended the Glendale Baptist Church where our parents were faithful Christians, supporting the Church with their tithes/offerings and attendance. We were taught by word and example, to be faithful to the Lord and His Church. Our Pastor and most all visiting Preachers were frequent guests at our meal table. In 1932 our mother organized and founded the Glendale Pentecostal Church which got it’s beginning in a tent revival located in our front yard. For a few years, Albert and I attended the church with her before returning back to the Baptist Church where our dad continued to attend, serving as a Deacon, Treasurer and Teacher.

From time to time, neighbors would say to our mother, you must have your hands full with five boys. She did! We were “all boy” and behaved like boys. We were forever pulling tricks on one another. We had a pet billy goat under which one of the boys threw a firecracker one day, when the firecracker popped, the goat jumped through the kitchen’s end glass window, skidded about 18 feet across the room, turning the table over, smashing the kitchen cupboard and bursting quite a few dishes. Yes, there were disagreements between us boys which led to a tumble or two from time to time, but we loved one another dearly and would have fought a circle saw in trying to protect one another. Proverbs 15; 17“Better is a dinner of herbs where love is, than a stalled ox and hatred therewith” This writer’s version; “better is a dinner of cornbread and turnip greens with love, than beef steak and gravy with malice”.

I was a junior in Frank Evans High School in Spartanburg when I entered public work. Dad and I were down in the woods getting pine needles for the cattle stalls when H. Lee Smith, owner of Smith Dry Cleaners in Spartanburg came down into the woods in his long black Cadillac to see if I would drive his city pick up/delivery truck after school hours. Leaving the farm behind and starting the next week, I took the part time job thus beginning my life of public work. A price war started among the dry cleaning establishments while I was with Smith Cleaners. H. Lee Smith, determined that no one would out do him, had a 10 X 18 or 20 foot sign painted on the side of his building overnight. In large bold letters it read, pants-jackets dry cleaned, 19 cents; dresses-suits dry cleaned, 39 cents or three for a dollar.

One thing I remember well about those days on the farm, we had some of the best neighbors to be found anywhere. Living in front of our house was the Luther McKinney family, the Charlie Sam’s family, the John Hunter and Elbert Pierce families. To our north were the George Willis and Henry Martin families. To our south was the John Thompson, the Landrum Thomas, the Jack McKinney families, Doctor Smith and Lillie Hayes, the community doctor and nurse. Behind our house were 4 black families, Henry Patton, Norman Lewis, Dan Dillard and Bud Murphy families. That’s when neighbors all knew one another and cared for one another. We were all just like one big family!

Ah! Those were the days! Money can’t buy the memories of my experience of “growing up on the farm”. Dad and Mama couldn’t give us all the things other boys may have had but they saw that we got what we needed. Most of all, they gave us their unconditional love for which we were all grateful. Thanks unto God for His manifold blessings and for our wonderful parents, who taught by example what it meant to be a real Christian.

This web site has been started as a public service to share the story of Glendale. See more information about Mary and her Glendale connection at Mary McKinney Teaster.